As a Real Estate Tax Strategist, I review thousands of tax returns each year that were both self-prepared, and prepared by other firms. Over the years I’ve noticed a really common area for mistakes is depreciation.

This blog is intended to be used as a checklist for what to look at on your depreciation schedule, and what to ask your tax professional if things don’t match up.

Reporting Rental income:

If you have any income that is generated by a long-term rental property owned by you personally, or by your single member LLC, you report it on Schedule E of your 1040.

See links here: Schedule E for 2021; IRS Tips on Rental Reporting

You are allowed to deduct all ordinary and necessary expenses related to your property, including depreciation.

Many tax firms do not provide a depreciation schedule with their default “Client Copy” of a tax return. If you receive your tax return and it does not include a Depreciation Schedule, ask to be provided with it before you sign off on the return.

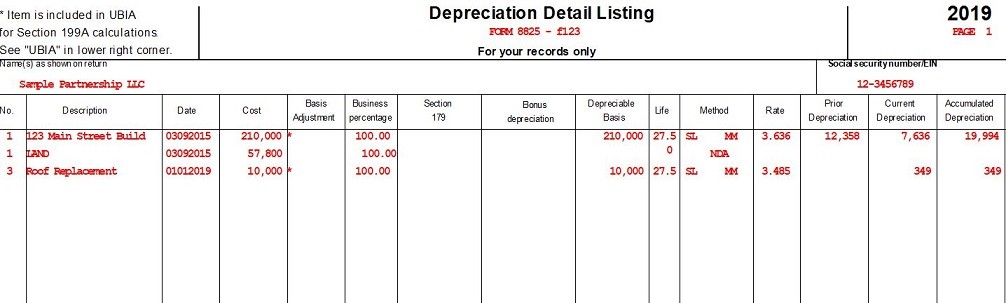

It is almost always a horizontal schedule, and lists the assets, dates, lives, and prior depreciation amounts for each. (See example below.)

What is Depreciation:

When you own a rental property you are allowed to depreciate the value of the building. What this means is you get to write off a portion of its value every year, according to a useful life the IRS decided.

See IRS Publication 527 for more information.

For standard long term residential rentals, this is 27.5 years. The thought here is that as an asset age, it should decline in value. We all know this isn’t necessarily the case with real estate, but it’s the tax law none the less.

We love depreciation because it’s what sometimes allows rental properties to show a loss on paper, even if a property cash flows. Additionally, many lenders add back depreciation when calculating your qualifying income.

Example:

A rental earned $10,000 in rents over the year and had $7,000 in expenses. At the end of the year there would be $3,000 of actual profit remaining in the bank account. For tax purposes however, we find out that our annual depreciation is $4,500. So, on your Schedule E, your reportable amount is a tax loss of $1,500.

| $10,000 | Rents |

| -$7,000 | Less: Expenses |

| $3,000 | =Cash Profit |

| -$4,500 | Less: Depreciation* |

| -$1,500 | =Net Passive Loss |

*Depreciation: a paper expense, no cash outflow incurred to be able to write this off

Here are the five things you need to review on your Depreciation Schedule:

1. Check the Amounts Listed

The first thing you should review when looking at your depreciation schedule is the overall amounts. It’s important to keep in mind that some closing costs, inspection costs, and due diligence fees will also be included in your “depreciable basis”—so it won’t always equal your purchase price. Actually, it should almost never equal exactly your purchase price. With this in mind, look at the overall total for the combined depreciable building value and land value. If these two amounts equal $100,000 but you know your purchase price alone was $150,000, ask your professional.

Example of an actual error:

One of the most common ways to figure out how much to allocate to land vs. building value is to apply the same ratio as the county tax assessor. The RATIO not the actual values.

The prior tax preparer used the actual county land value of $52,000 vs. applying a ratio. This resulted in a total basis of $110,258 for building and $52,000 for land. The problem: The client had only paid a total of $120,000 for the entire property. This mistake accidentally gave the client an extra $50,000 of basis in their rental.

2. Land Value Backed Out

Make sure the amount of land value is backed out of the amount being depreciated. We can not depreciate land. So, if you know you paid $60,000 for a rental, and all $60,000 is listed as the depreciable amount, something is wrong.

As mentioned above, the most common method to utilize is the same ratio as the county assessor.

Example of an actual error:

The prior tax preparer listed no land value of the depreciation schedule. The amount of building value to be depreciated was listed as $249,000. Upon comparing against the HUD/Purchase document–this was the full purchase price of the property. This resulted in the client incorrectly receiving an extra $1,759 write off every year for multiple years, and a nasty amount owing when it was corrected.

3. Renovations

If you did a major renovation, see if it is listed as a lump sum amount on the depreciation schedule. If you spend $40,000 on a renovation that included $10,000 of landscaping, and $5,000 on new appliances, there may be a more advantageous way to report it. A major renovation is assumed to be a 27.5-year improvement—same as the actual building of a rental. However, there are certain things that have been specifically assigned shorter lives. Landscaping for example, falls into a category known as land improvements which have a life of 15 years. To add on that, any assets with a life of less than 20 years can potentially be expensed all in year one using bonus depreciation. There are lots of potentials with renovations, and this is a great conversation to have with your tax professional.

Example of an actual error:

A client who was a real estate professional (meaning they could deduct unlimited rental losses) had been buying 2-3 new rentals each year, completing major renovations on each. The prior depreciation schedule listed “$82,000 Renovations –27.5 year”, or something very similar, for every property. Resulting in a depreciation deduction of $2,980 for the year.

In the current year however, we broke out what was done in their major renovations. So instead, it looked like this.

| $8,000 | Landscaping @ 15 years |

| $6,200 | Appliances @ 5 years |

| $2,000 | New Fence @ 15 years |

| $16,200 | Total Assets* |

*Total Assets: Assets with a life of less than 20 years, qualifying for year 1 Bonus Depreciation

| $63,800 | Major renovation 27.5 years |

Resulting in a current year depreciation deduction of $18,520.

4. Delayed Financing Hang up

If you do delayed financing (Alex Felice’s podcast) where you put your renovation costs INTO escrow when you purchase, your tax professional may be shortchanging you on depreciation. This is because many tax professionals do not realize the structure of this transaction, and they are taking the full renovation amount and lumping it into the purchase price, since it all appears on the purchase documents. They are then allocating that total amount between land vs. building.

This is incorrect because the allocation should only apply to the purchase price–then the renovation amount should be accounted for separately.

Example of an actual error:

The client’s prior CPA would take the full amount of his HUD where they prepaid renovation costs to allow for earlier refinancing via the BRRRR method as his purchase price. So his purchase HUD’s would show $30,000 purchase price $40,000 renovation escrow (ignoring misc. closing costs).

So their initial depreciation was calculated as:

- $70,000 Purchase price * the 82% building value per the tax assessor = $57,400 depreciable value at 27.5 years for a deduction of $2,087 per year

When it should have been:

- $30,000 purchase price * 82% building value per the tax assessor = $24,600 depreciable value at 27.5 years for a deduction of $895 per year

AND

- $40,000 renovation value (which could have likely been broken down further as described above) at 27.5 years for a deduction of $1,454 per year

- For a total annual Depreciation of $2,350 per year.

This doesn’t seem huge—but this client had close to ten properties that were all setup using this incorrect method, resulting in a lost depreciation deduction of close to $4,000 per year, across multiple years. We were able to correct utilizing form 3115 and recoup that deduction.

5. Review the Dates

Your rental is able to begin being depreciated when it is “In Service”. This means when it is ready and available for rent. (Not necessarily rented). Also important to note, if you buy a rental with tenants in it, issue them a 60 day notice to vacate, then spend 90 days on a renovation, the property is “in service” that entire time. Normal vacancies or spans of non-occupancy for renovation do not take a property out of service.

Review the dates listed for your rental asset and renovation dates. Many preparers will ask for an in-service date but not ask if the rental was occupied when first purchased. And many tax professionals will just utilize the purchase date. If a property is purchased vacant on January 1st but requires a six month renovation, it is not “in service” until the end of that six months.